With the dollar turning into a safe haven during the pandemic, risk appetite has become one of the most crucial elements for the FX market. The other main variable is interest rate differentials. In this piece we examine how much firepower each central bank has unleashed and what that implies for currencies. The Fed has been quite aggressive in this crisis, but Japan is the undisputed leader overall. Looking ahead, the ECB could deliver even more, whereas the Fed may have fired its final shot.

The QE era

Changes in interest rates between economies have always governed exchange rates. Money flows gravitate towards the higher rate regime as investors search for yield, so when a central bank signals it will be raising borrowing costs, its currency tends to appreciate. In contrast, signals for lower rates typically harm a currency.

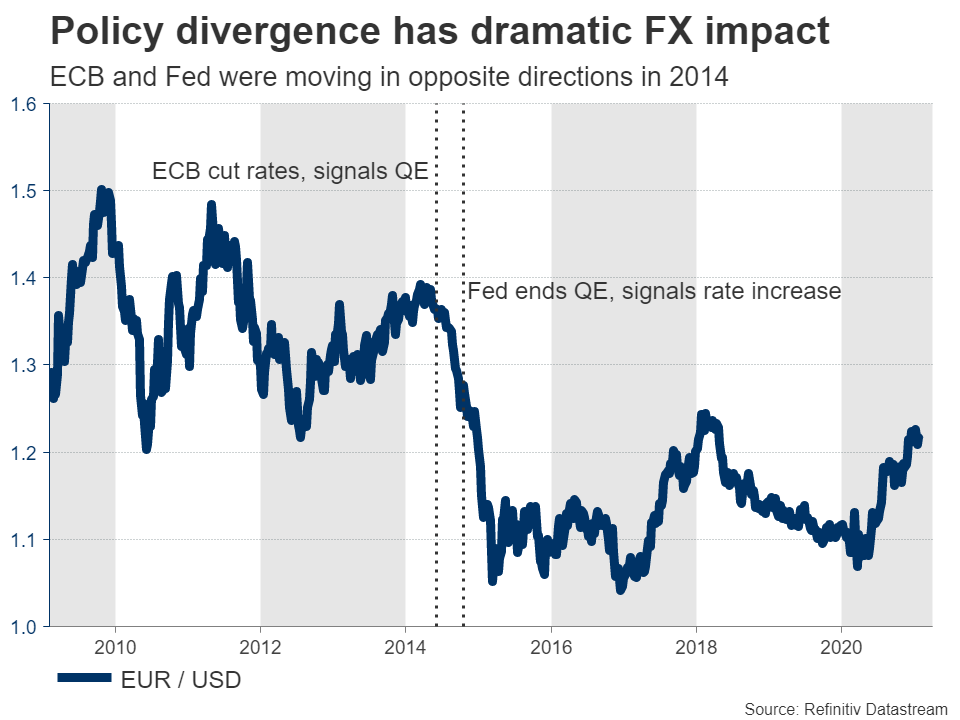

Some of the biggest FX moves happen when two economies go in opposite directions in their monetary settings. For instance, euro/dollar collapsed in 2014 as it became clear that the Fed would be raising interest rates soon whereas the European Central Bank was ready to experiment with QE for the first time.

Quantitative Easing (QE) is a process by which a central bank can push borrowing costs lower. When interest rates are already at zero but policymakers want to stimulate the economy further, they can start buying government bonds. Through massive purchases of these bonds, the yields on them fall, making it easier for governments to service their debt and spend more today.

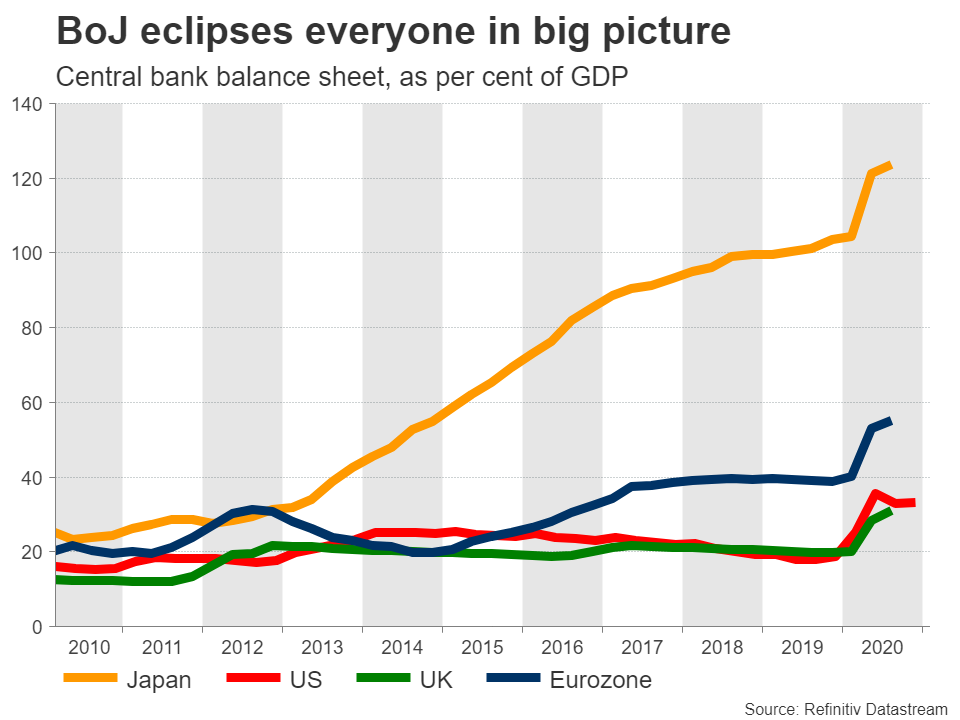

This is the name of the game nowadays. With every major central bank having slashed rates to zero or below, it is the size of these QE purchases that mostly impacts currencies in this era. The more a central bank buys, the more its currency suffers, in theory. In reality, other factors can negate this downward pressure, as Japan has shown the world.

Fed: Go big and go early

In the US, the Fed has been especially bold during the pandemic. It cut rates from near 2% to almost zero and started buying $120bn per month in government bonds, mortgage-backed securities, and even some corporate bonds, to push longer-term borrowing costs down for the government and big corporations.

Its powerful actions were crucial in sinking the dollar, as it was buying much more than the ECB and the Bank of Japan. The other element was the improvement in risk sentiment. Once it became clear that the sky was not falling, investors lost their appetite for hoarding dollars defensively.

That said, the Fed’s most aggressive days are probably behind it. The US economy is much stronger than most of its rivals, is doing relatively well in the vaccination race, and there’s a volley of spending coming from Congress just for good measure.

The Fed’s next move will probably be to start reducing its monthly QE purchases, perhaps by early 2022. The markets could start to price in this shift much earlier, possibly by the middle of this year, at which point the dollar could really begin to shine.

ECB not at the final act yet

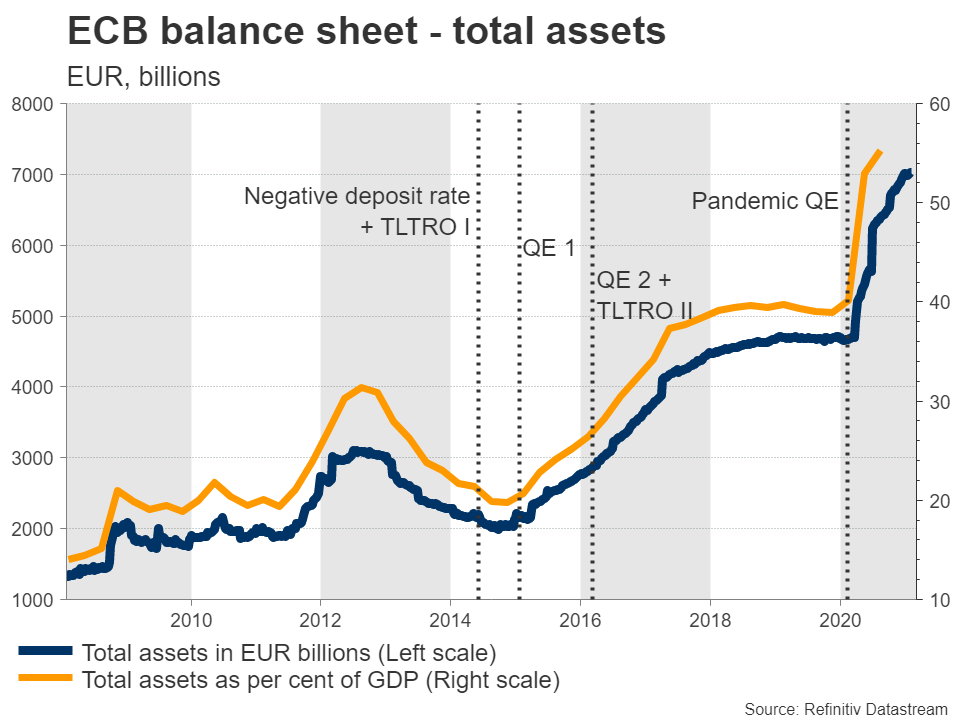

Across the Atlantic, the European Central Bank has been quite reserved during the pandemic, though it has accumulated massive amounts of bonds over the years, amounting to 55% of the Eurozone’s GDP as of the third quarter of 2020. The amount of its purchases per month varies depending on market conditions, but lately the total has been around €50-70bn a month.

Beyond buying government and corporate bonds, the ECB has also showered the banking sector in cheap money, through generous long-term loans called TLTROs. The Bank offers these loans to financial institutions at below market rates to encourage them to lend out more.

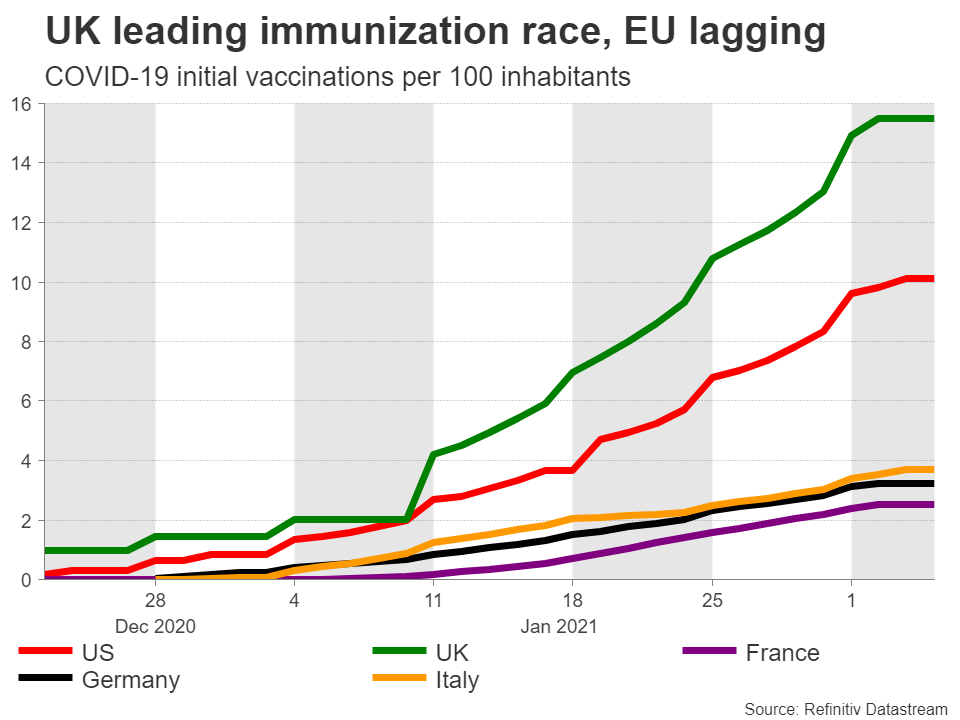

In contrast to the Fed, the ECB may not have fired its last shot yet. Most of the Eurozone is still in a harsh lockdown and the bloc has fallen way behind in the global vaccination race. The economy seems to be headed for a double-dip recession, and there isn’t any impressive government spending in the pipeline either to cushion the blow.

This suggests the ECB could be forced to open the QE taps even wider at some point, or at least that it will be among the last to scale back its purchases. There is not much to be optimistic about in Europe, and the narrative of US economic outperformance – and thus of ECB/Fed divergence – could become a dominant FX driver going forward, keeping the risks surrounding euro/dollar tilted to the downside.

Swift immunization pace allows BoE to step back

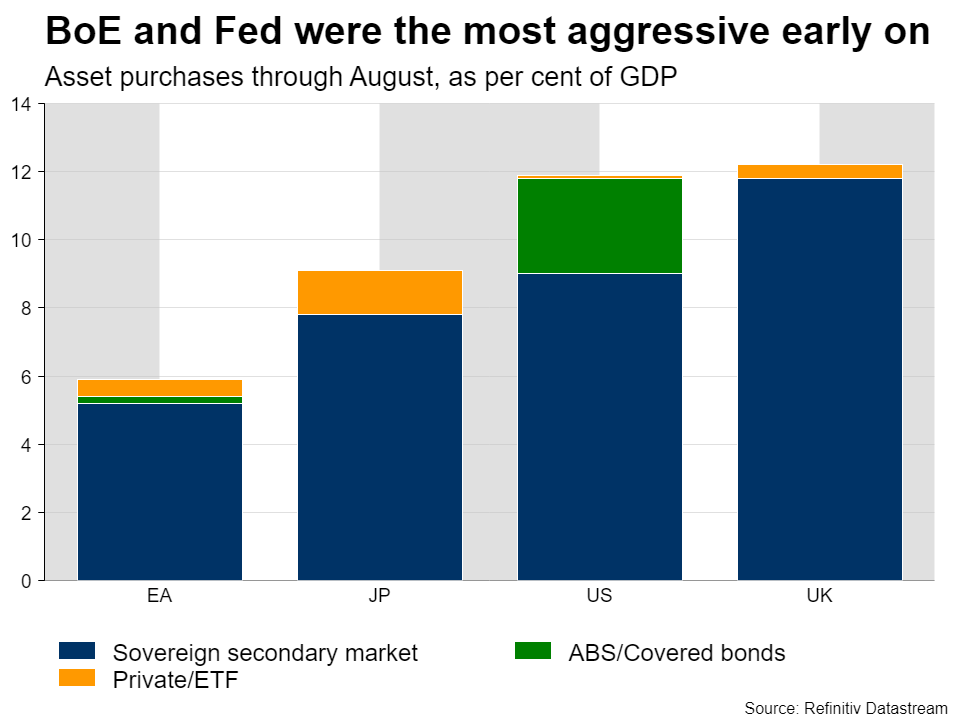

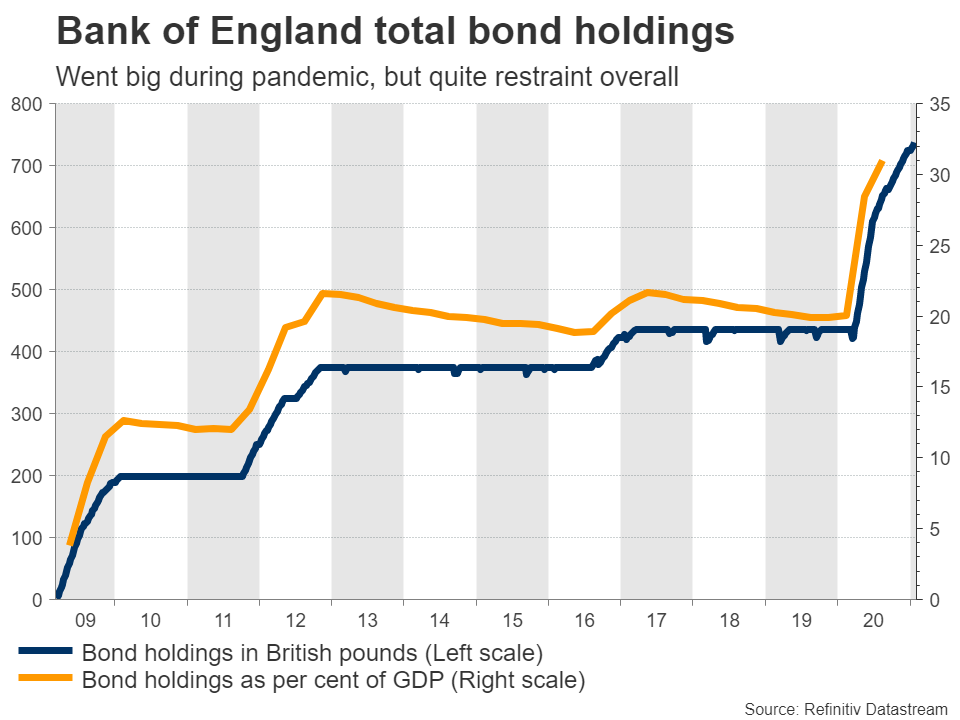

Staying in Europe, the Bank of England was surprisingly the most aggressive in terms of QE purchases relative to the size of its economy during the early stages of this crisis. In the bigger picture, however, it has been the least aggressive. Its total purchases over the years amount only to 31% of British GDP as of Q3 2020, far less than the Eurozone or Japan.

It has purchased £736bn of government and corporate bonds so far, out of a total envelope of £895bn that policymakers have approved. At the current buying pace of around £10-20bn per month, this would imply that the Bank would have to expand the program again towards the end of the year.

But will it? A strong argument can be made that if the UK continues to vaccinate its population at such a rapid pace, the Bank won’t need to extend the QE program again. Nor is it likely to cut rates to negative territory, for fear of kneecapping the nation’s enormous financial industry. Simply saying that negative rates are an option is enough to deliver some of the easing benefits, without suffering the costs of that policy, which is exactly what the BoE is doing.

In FX terms, the outlook for the pound seems promising, especially against the euro. The UK economy might ‘return to normal’ much faster than the Eurozone, and the case for negative rates is likely to fade as the economy picks up. The main downside risk is whether the existing vaccines will be effective against all the mutated strains of covid. If some variants prove to be highly resistant to vaccines, this cheerful narrative could take a severe blow.

Bank of Japan unable to torpedo yen

The BoJ has not gone all-out during the pandemic, but over the years, it has been the most interventionist central bank by far. Its total balance sheet amounts to a stunning 128% of GDP, made up mostly of government bonds and stock market ETFs. Its stock market interventions have been so heavy that the BoJ has become the biggest shareholder of most large Japanese businesses.

Beyond buying a truckload of bonds and stocks, the Bank has also enacted negative interest rates, as well as a yield curve control strategy that keeps 10-year Japanese bond yields anchored at 0%. It is essentially a QE program on steroids.

One might ask then, why hasn’t the yen collapsed under the weight of such powerful actions? The answer lies with the nation’s gigantic current account surplus. Japan is the world’s biggest creditor nation, meaning that it exports much more than it imports, which fuels demand for its currency. This is also part of what makes the yen a safe haven. When the global economy is in trouble, Japanese investors tend to repatriate funds from abroad, boosting the yen.

Looking ahead, there’s some speculation that the BoJ might allow Japanese yields to move in a wider range, to support financial institutions that suffer from ultra-low rates. This would be a de-facto tightening move. However, with deflationary forces growing stronger, this is not the time to be withdrawing support. If the BoJ goes ahead with this move, it will most likely accompany it with some other easing strategy to keep the overall stance of policy constant.

As for the yen, with the BoJ having expended most of its firepower, the currency’s fate hangs mostly on external forces now. The biggest variable will be whether the global vaccine rollout proceeds smoothly. If expectations for a powerful global recovery come to fruition, the defensive yen could lose ground against currencies whose central banks may begin to scale back QE programs, like the dollar and pound.

– FX.Com